Headaches are 1 of the top 5 health problems of childhood.Because 58.4% of children and adolescents aged 1 month or older will develop will develop headaches at some point, general pediatric practitioners may have many opportunities to evaluate and treat patients with headaches

Πονοκέφαλος στα παιδιά

Οι πονοκέφαλοι στα παιδιά είναι συχνοί και συνήθως δεν είναι σοβαροί. Όπως οι ενήλικες, τα παιδιά μπορεί να αναπτύξουν διαφορετικούς τύπους πονοκεφάλων, συμπεριλαμβανομένων των ημικρανιών ή των πονοκεφάλων (τασης) που σχετίζονται με το στρες. Τα παιδιά μπορεί επίσης να έχουν χρόνιους καθημερινούς πονοκεφάλους.

Σε ορισμένες περιπτώσεις, οι πονοκέφαλοι στα παιδιά προκαλούνται από μόλυνση, υψηλά επίπεδα στρες ή άγχους ή τραύμα στο κεφάλι. Είναι σημαντικό να δίνετε προσοχή στα συμπτώματα πονοκεφάλου του παιδιού σας και να συμβουλευτείτε έναν γιατρό εάν ο πονοκέφαλος επιδεινώνεται ή εμφανίζεται συχνά.

Οι πονοκέφαλοι στα παιδιά συνήθως μπορούν να αντιμετωπιστούν με παυσίπονα χωρίς ιατρική συνταγή (OTC) και υγιεινές συνήθειες, όπως ένα τακτικό πρόγραμμα ύπνου και φαγητού.

Οι περισσότεροι πονοκέφαλοι δεν είναι σοβαροί, αλλά αναζητήστε άμεση ιατρική φροντίδα εάν οι πονοκέφαλοι του παιδιού σας:

- Ξυπνούν το παιδί σας από τον ύπνο

- Επιδεινώνονταιται ή γίνονται πιο συχνοί

- Προκαλούν αλλαγές στην προσωπικότητα του παιδιού σας

- Αν εμφανιστούν μετά απο έναν τραυματισμό, όπως ένα χτύπημα στο κεφάλι

- Συνοδεύονται απο επίμονους εμετούς ή οπτικέςδιαταραχές

- Συνοδεύονται

από πυρετό και πόνο στον αυχένα ή δυσκαμψία

Τύποι κεφαλαλγίας

Πρωτοπαθής χωρίς συνυπάρχοντα αίτια

Δευτεροπαθής ή οργανική, που είναι αποτέλεσμα:

• Πυρετού, φυσικής καταπόνησης, έκθεσης στον ήλιο, λοιμώξεων ( μηνιγγίτιδα, ωτίτιδα, ιγμορίτιδα)

• Κρανιοεγκεφαλικών κακώσεων

• Αγγειακής αιμορραγίας

• Χωροκατακτητικών εξεργασιών

• Δηλητηριάσεων με φαρμακευτικές ουσίες

• Άγχους

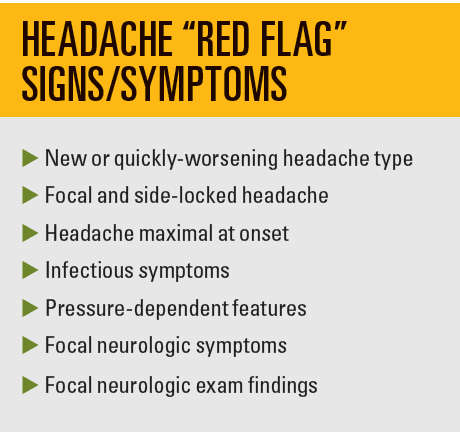

Urgent versus nonurgent headaches

Many conditions can present initially with headache, so it is important to have a list of “red flag” risk factors, symptoms, and exam findings to keep in mind during the initial assessment. Red flag risk factors would include a patient aged younger than 6 years, history of neurocutaneous syndrome, systemic illness, immunodeficiency, known malignancy, or hypercoagulability.2

Red flag symptoms include new (< 1 month) or quickly worsening headache type, focal and sidelocked headache, headache maximal at onset (thunderclap headache), infectious symptoms (eg, fever, meningismus, sinus or ear pain), or pressure-dependent features (eg, positional headache), headache worse in the middle of the night or first thing in the morning, headaches triggered by cough or Valsalva maneuvers, vomiting that is persistent and increasing in frequency. Focal neurologic symptoms or exam findings (eg, seizures, vision changes, papilledema, ataxia) also require urgent evaluation. Etiologies that cannot be missed include mass lesions, infections (eg, meningitis/encephalitis, brain abscess), and vascular etiologies (eg, stroke, hemorrhage, aneurysm, arteriovenous malformation, cerebral venous sinus thrombosis). Any of these symptoms or exam findings should prompt urgent consideration of brain imaging and/or lumbar puncture. Less than 1% of brain abnormalities in patients present with chronic headache as the only symptom.3

Primary versus secondary headaches

Once urgent headache etiologies are no longer of concern, the next objective is to distinguish between primary and secondary headaches. Unlike secondary headaches, primary headaches, such as migraine and tension-type headaches, are not a symptom of an underlying issue. Whereas a child may develop migraine-type headaches due to obstructive sleep apnea, the diagnosis of primary headache is only made after excluding the possibility of a secondary headache disorder. Depending on the history and physical exam, as well as diagnostic testing when needed (eg, screening blood tests or sleep study), the differentiation between primary and secondary headache can be made.

Primary headaches

The diagnosis of primary headache is made primarily through identifying classic characteristics of the headache, as there are no confirmatory diagnostic tests. The International Headache Society has created an International Classification of Headache Disorders to aid clinicians and investigators.4,5

The diagnosis of episodic childhood migraine is adapted from adult migraine. It is defined as an episodic headache with 5 or more attacks that last 2 to 72 hours. It must have 2 or more of the following: unilateral or bilateral location, pulsating quality, moderate to severe pain, or aggravation by routine physical activity. It must also have 1 or more of the following: nausea or vomiting, and photophobia and phonophobia. For childhood migraine, experts argue that headaches are often shorter, lasting 30 minutes or more, and often fitting 1 or more of each category.6 Premonitory signs also are different in childhood migraine than in adult migraine. They are most commonly fatigue, mood changes, neck stiffness, cranial autonomic symptoms, and cutaneous allodynia, rather than visual disturbance or dizziness.7

Diagnosing episodic childhood tension-type headache requires 10 or more episodes lasting from 30 minutes to 7 days. It must have 2 or more of the following: bilateral location, pressing or tightening quality (nonpulsating), mild or moderate intensity, and it cannot be aggravated by routine physical activity. There cannot be nausea or vomiting, and no more than 1 of photophobia or phonophobia.

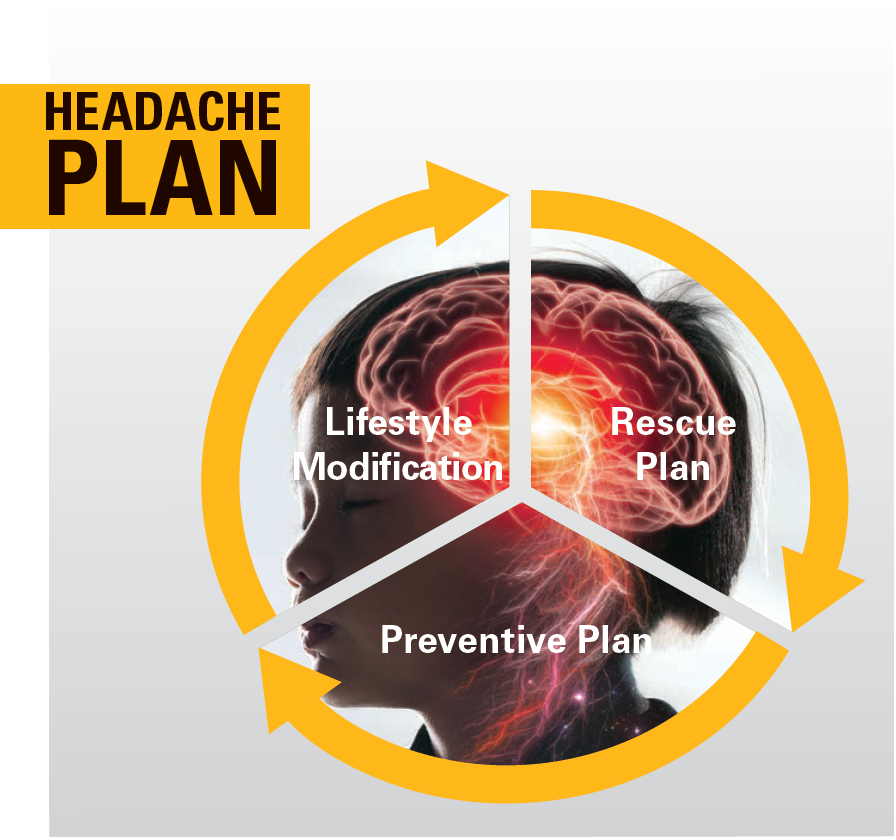

Children and adolescents may present with both migraine and tension-type headaches, making it difficult to have separate treatment trials. In fact, it is unclear whether they are actual separate biological entities.8 Most treatments are geared toward migraine management, but the overall approach for both should be 3-pronged, addressing lifestyle modifications, a rescue plan, and a preventative plan.

Headache treatment: Lifestyle modification

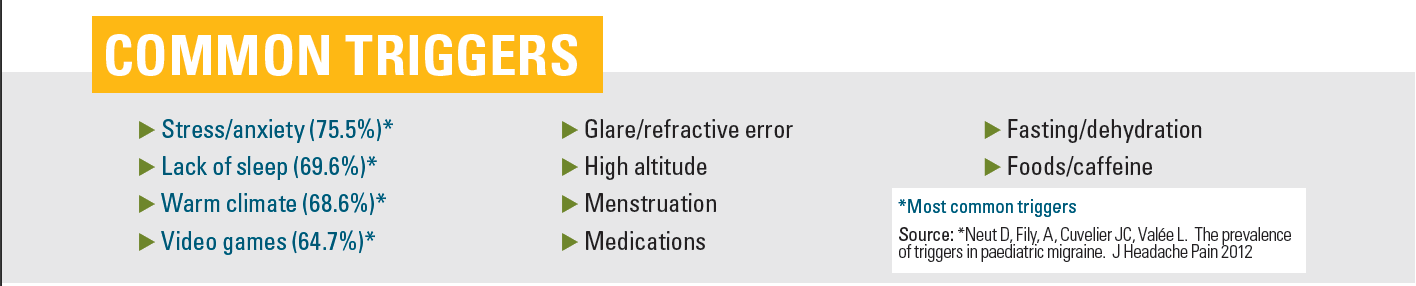

The most common triggers for childhood headache include stress/anxiety, lack of sleep, warm climate, and video games.9 Other triggers include glare, eye strain, high altitude, menstruation, medications, fasting, dehydration, certain foods (eg, simple sugars, smoked meats, chocolate), caffeine use, and lack of exercise.

The first step in headache treatment is to better characterize the headaches and triggers by keeping a headache diary documenting possible triggers, time of day, days per month, headache intensity, and response to treatment. The number and/or intensity of headaches over time influences what types of treatment are needed. For example, episodic headaches (less than 2 times a week) can be treated with rescue medications alone, whereas headaches more frequent than that will require preventative treatment as well as rescue medications.

The general categories for lifestyle modifications are water and food intake, sleep regulation, daily exercise, and stress reduction.

Headache treatment rescue plan

Tip: Tell patients and their caregivers that the rescue plan should be implemented right at the beginning of the headache.

Because of the nature of the headache/pain cycle with amplification over time, the longer it takes to treat, the harder it is to break the cycle. Taking rescue measures early and taking the full dose of the abortive medication are more effective than waiting and then giving a half dose followed by another half dose.

Caregivers should be cautioned that these medications are only meant for rescue. Taking them more than 2 or 3 times a week over a month-long period can lead to medication overuse headache syndrome.

Nausea and vomiting are most common in younger children as part of the headache syndrome,10 and antiemetics can be used in conjunction with headache medications. As patients who are nauseated may not tolerate swallowing pills, many headache medications come in oral-dissolving or intranasal formulations.

The first line for abortive headache treatments includes acetaminophen, ibuprofen, and other nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. Randomized trials for pharmacologic rescue treatments efficacy show acetaminophen at 54% and ibuprofen at 68.76%.11

Triptan medications, the second line for rescue headache treatments, were designed specifically to abort migraine headaches. Because they have selective activity on atypical 5HT1B and 5HT1D receptors, their mechanisms of action include cranial vasoconstriction, peripheral trigeminal inhibition, and inhibition of transmission via the trigeminal cervical complex. They are typically well tolerated. Common adverse effects include paresthesia, sleepiness, dizziness, and tightness in chest or throat. They should not be used more than 2 times a week and should be avoided in patients with cardiovascular disease, who are pregnant, or who have complicated migraines. Rizatriptan (efficacy 73-74%) is the only treatment approved for patients aged 6 to 12 years. Sumatriptan nasal spray (64-86%), combination sumatriptan/naproxen, almotriptan (72-73%), and zolmitriptan nasal spray (62%) are approved in patients aged 12 to 17 years.11

Further pharmacologic rescue treatments typically have to be administered intravenously in the emergency department setting. Of the dopamine antagonists, prochlorperazine (Compazine) IV is the most effective abortive in randomized trials at 84.8% pain relief, followed by metoclopramide (Reglan) and promethazine (Phenergan).12,13

Headache treatment-preventive plan

Whereas patients with episodic headache can often be treated with lifestyle changes and rescue medications alone, others with chronic headaches (> 15 days a month) and severe headaches will benefit from a preventive plan that aims to decrease both headache severity and frequency.

Tip: it is important to distinguish rescue from preventive treatment, so patients do not stop taking preventive treatments within few days when it “doesn’t work.”

Patients should understand that preventive treatment has to start at a low dose to minimize adverse effects and build up slowly. Within 6 to 8 weeks of taking it constantly, the goal would be a decrease in headache frequency and intensity by at least 50%.

For many years, the use of pharmacologic preventive medications in childhood headache was based on adult studies. A seminal paper published in The New England Journal of Medicine in 2018 based on the CHAMP trial (NCT01581281) compared children with episodic migraine in 3 prospective randomized groups taking placebo, topiramate 2 mg/kg, or amitriptyline 1 mg/kg.14 The trial was stopped early because the placebo group did as well as the other 2 groups with fewer adverse effects. It was noted that patients had an average of 11 days per month of headache (suggesting more of an episodic than chronic headache picture) and that the placebo group received appropriate lifestyle management and rescue plan counseling. This underscores the efficacy of lifestyle and rescue management independent of pharmacologic preventive therapy.

Following this study, many practitioners chose to offer nutraceuticals for headache prevention before going straight to pharmacologic treatments. Nutraceuticals include vitamins, minerals, herbal supplements, and dietary supplements. Magnesium, riboflavin (vitamin B2), coenzyme Q10, and vitamin D3 all have demonstrated efficacy in some pediatric trials for headache prevention,15-18 although there are limited studies with a placebo group. Importantly, the adverse effect profile for nutraceuticals is better than for pharmacologic agents.

If headaches continue to be troublesome despite lifestyle management, good rescue therapy, and a sustained trial of nutraceuticals, it is reasonable to consider pharmacologic preventatives. Cyproheptadine (Periactin), an antihistamine, has no clinical trial data but has probably been used the longest for pediatric headache prevention. Although it is well-tolerated in younger children, patients 8 years of age and older typically experience too much sedation for it to be acceptable. Topiramate, an epileptic medication, received FDA approval in 2014 for the prevention of headaches in adolescents aged 12 to 17 years. Potential common adverse effects include cognitive slowing, paresthesias, appetite suppression, and renal stones. Amitriptyline, an antidepressant, can be helpful for patients with migraines who also have insomnia and/or depression. Besides somnolence, it can cause appetite increase, tachycardia, and dry mouth. Propranolol, a β-blocker, has 1 randomized control trial from 1974 showing efficacy, but subsequent studies have been negative. Possible adverse effects include exercise intolerance, depression, and light-headedness.

Finally, there are many other nonpharmacologic interventions that have been shown to be helpful in mitigating childhood headache and may have a synergistic effect with preventive medications. Cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) in combination with amitriptyline was more beneficial than CBT alone for a group of adolescents.19 There is some convincing evidence for biofeedback (teaching patients to regulate physical responses to stress) in the prevention of pediatric migraine, sometimes in combination with relaxation therapy. At Stanford Children’s Health, occupational therapists and pediatric pain psychologists are trained in multiple modalities such at CBT, biofeedback, and relaxation therapy. If there is a history of neck/shoulder pain or tenderness to palpation of the scalp, neck, or shoulders, a physical therapist can help strengthen and realign a patient’s posture to prevent cervicogenic headache. There is 1 positive study on acupuncture for pediatric headache,20 and many adult studies demonstrate efficacy in chronic pain and headache. It is important to explain to the patient that acupuncture needles are much thinner and less painful than typical needles; children who have had acupuncture before seem to prefer this method.

When to refer to a neurologist

Instances in which consultation with a neurologist could be helpful would include headaches that are severe, prolonged, or intractable. Neurology consultation would be indicated for patients with a complicated aura (eg, hemiplegic migraine or migraine with brainstem symptoms such as dysarthria, vertigo, tinnitus, or diplopia). Referral is advised when a pediatric practitioner is reconsidering the diagnosis of primary headaches and would like guidance on workup for secondary headaches. Finally, a practitioner may feel comfortable implementing first- or second-line therapies but will seek help with less conventional treatments, such as the new class of anti-cGRP monoclonal antibodies. These have not yet been approved in children but are increasingly being prescribed off label for adolescents with intractable migraines. The American Headache Society Section on Pediatric-Adolescent Headache offers guidelines for administering these new treatments.21 Several neuromodulatory devices have been developed for the headache population, with 2 approved by the FDA for adolescents, but the studies have very small sizes (9-45 patients) and the cost for renting these devices is often prohibitive.

Childhood headache can be dangerous, debilitating, or both. After excluding dangerous causes, it is important to provide the patient and caregiver with a plan for headache management that includes education on lifestyle management, rescue plan, and preventive measures. During the current pandemic, screen time and eye strain have become more significant triggers, whereas, conversely, being able to sleep in later on school days appears to be beneficial for teenagers.22,23 The more that children and their caregivers are empowered to understand and manage childhood headaches, the better for all involved.

SOURCES: CONTEMPORARY PEDIATRICS, MAYO CLINIC,AAP

References

- Abu-Arafeh I, Razek S, Sivaraman B, Graham C. Prevalence of headache and migraine in children and adolescents: a systematic review of population-based studies. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2010;52(12):1088-1097. doi:10.1111/j.1469-8749.2010.03793

- Parisi P, Papetti L, Spalice A, Nicita F, Ursitti F, Villa MP. Tension-type headache in paediatric age. Acta Paediatr. 2011;100(4):491-495. doi:10.1111/j.1651-2227.2010.02115.x

- Abu-Arafeh I, McLeod S. Serious neurologic disorders in children with chronic headache. Arch Dis Child. 2005;90(9):937-940. doi:10.1136/adc.2004.067256

- Headache Classification Committee of the International Headache Society (IHS) The International Classification of Headache Disorders, 3rd edition. Cephalalgia. 2018;38(1):1-211. doi:10.1177/0333102417738202

- Guidelines. International Headache Society. Accessed February 27, 2021. https://ihs-headache.org/en/resources/guidelines/

- Özge A, Faedda N, Abu-Arafeh I, et al. Experts’ opinion about the primary headache diagnostic criteria of the ICHD-3rd edition beta in children and adolescents. J Headache Pain. 2017;18(1):109. doi:10.1186/s10194-017-0818-y

- Karsan N, Prabhakar P, Goadsby PJ. Characterising the premonitory stage of migraine in children: a clinic-based study of 100 patients in a specialist headache service. J Headache Pain. 2016;17(1):94.doi:10.1186/s10194-016-0689-7

- Monteith TS, Sprenger T. Tension type headache in adolescence and childhood: where are we now?Curr Pain Headache Rep. 2010;14(6):424-430. doi:10.1007/s11916-010-0149-z

- Neut D et al. The prevalence of triggers in paediatric migraine: a questionnaire study in 102 children and adolescents. J Headache Pain. 2012;13(1):61-65. doi:10.1007/s10194-011-0397-2

- Wilcox SL, Ludwick AM, Lebel A, Borsook D. Age- and sex-related differences in the presentation of paediatric migraine: A retrospective cohort study. Cephalalgia. 2018; 38(6):1107-1118. doi:10.1177/0333102417722570

- Gelfand A, Goadsby PJ. Treatment of pediatric migraine in the emergency room. Pediatr Neurol. 2012;47(4):233-241. doi:10.1016/j.pediatrneurol.2012.06.001

- Sheridan DC, Laurie A, Pacheco S, et al. Relative effectiveness of dopamine antagonists for pediatric migraine in the emergency department. Pediatr Emer Care. 2018;34(3):165-168. doi:10.1097/PEC.0000000000000718

- Bachur RG, Monuteaux MC, Neuman MI. A comparison of acute treatment regimens for migraine in the emergency department. Pediatrics. 2015;135(2):232-238. doi:10.1542/peds.2014-2432

- Powers SW, Coffey CS, Chamberlin LA, et al. Trial of amitriptyline, topiramate, and placebo for pediatric migraine. N Engl J Med. 2017;376(2):115-124. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1610384

- Wang F, Van Den Eeden SK, Ackerson LM, Salk SE, Reince RH, Elin RJ. Oral magnesium oxide prophylaxis of frequent migrainous headache in children: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Headache. 2003;43(6):601-610. doi:10.1046/j.1526-4610.2003.03102.x

- Das R, Qubty W. Retrospective observational study on riboflavin prophylaxis in child and adolescent migraine. Pediatric Neurology. 2021;114:5-8. doi:10.1016/j.pediatrneurol.2020.09.009

- Slater SK, Nelson TD, Kabbouche MA, et al. A randomized, double-blinded, placebo-controlled, crossover, add-on study of coenzyme Q10 in the prevention of pediatric and adolescent migraine. Cephalalgia. 2011;31(8):897-905. doi:10.1177/0333102411406755

- Fallah R, Yazd SS, Sohrevardi SM. Efficacy of topiramate alone and topiramate plus vitamin D3 in the prophylaxis of pediatric migraine: a randomized clinical trial. Iran J Child Neurol. 2020;14(4):77-86. doi:10.22037/ijcn.v15i1.18017

- Powers SW, Kashikar-Zuck SM, Allen JR, et al. Cognitive behavioral therapy plus amitriptyline for chronic migraine in children and adolescents: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2013;310(24):2622-2630. doi:10.1001/jama.2013.282533

- Pintov S, Lahat E, Alstein M, Vogel Z, Barg J. Acupuncture and the opioid system: implications in management of migraine. Pediatr Neurol. 1997;17(2):129-133. doi:10.1016/s0887-8994(97)00086-6

- Szperka CL, VanderPluym J, Orr SL, et al. Recommendations on the use of anti-CGRP monoclonal antibodies in children and adolescents. Headache. 2018;58(10):1658-1669. doi:10.1111/head.13414

- David A, Wujack T. Doctors seeing more eye strain and headaches from virtual learning and screen time during pandemic. WXYZ. December 4, 2020. Accessed March 19, 2021. https://www.wxyz.com/rebound/doctors-seeing-more-eye-strain-and-headaches-from-virtual-learning-and-screen-time-during-pandemic

- Gelfand AA, Pavitt S, Ross AC, et al. Later high school start time is associated with lower migraine frequency in adolescents. Headache. 2021;61(2):343-350.doi:10.1111/head.14016